Date of Entry Dachau Concentration Camp (following Kristallnacht).

November 11, 1938.

Isaak Beck. Prisoner 20,834. Release date 22 Nov 1938.

Ludwig Beck. Prisoner 20,898. Release date 22 Nov, 1938.

Walter Beck. Prisoner 20,899. Release date 6 Jan 1939.

Adolf Reutlinger. Prisoner 20,911. Release date 12 Jan 1939.

Samuel Beck. Prisoner 21,859. Release date 22 Nov 1938.

Sigfried Geismar. Prisoner number 22,396. Release date 22 Dec 1938.

Our journey to Dachau, where our ancestors endured unimaginable hardships in 1938, was both a haunting and essential part of our family history exploration. We approached the visit with mixed emotions – eager to understand the camp’s history, but also with a heavy heart.

Throughout our travels, we had retraced the footsteps of our family’s past, but this was our first encounter with one of the infamous concentration camps. The memories of Kristallnacht, a dark chapter in November 1938 that led to the arrest of thousands of Jewish men, including our grandfather, great-grandfather, uncles, and cousins.

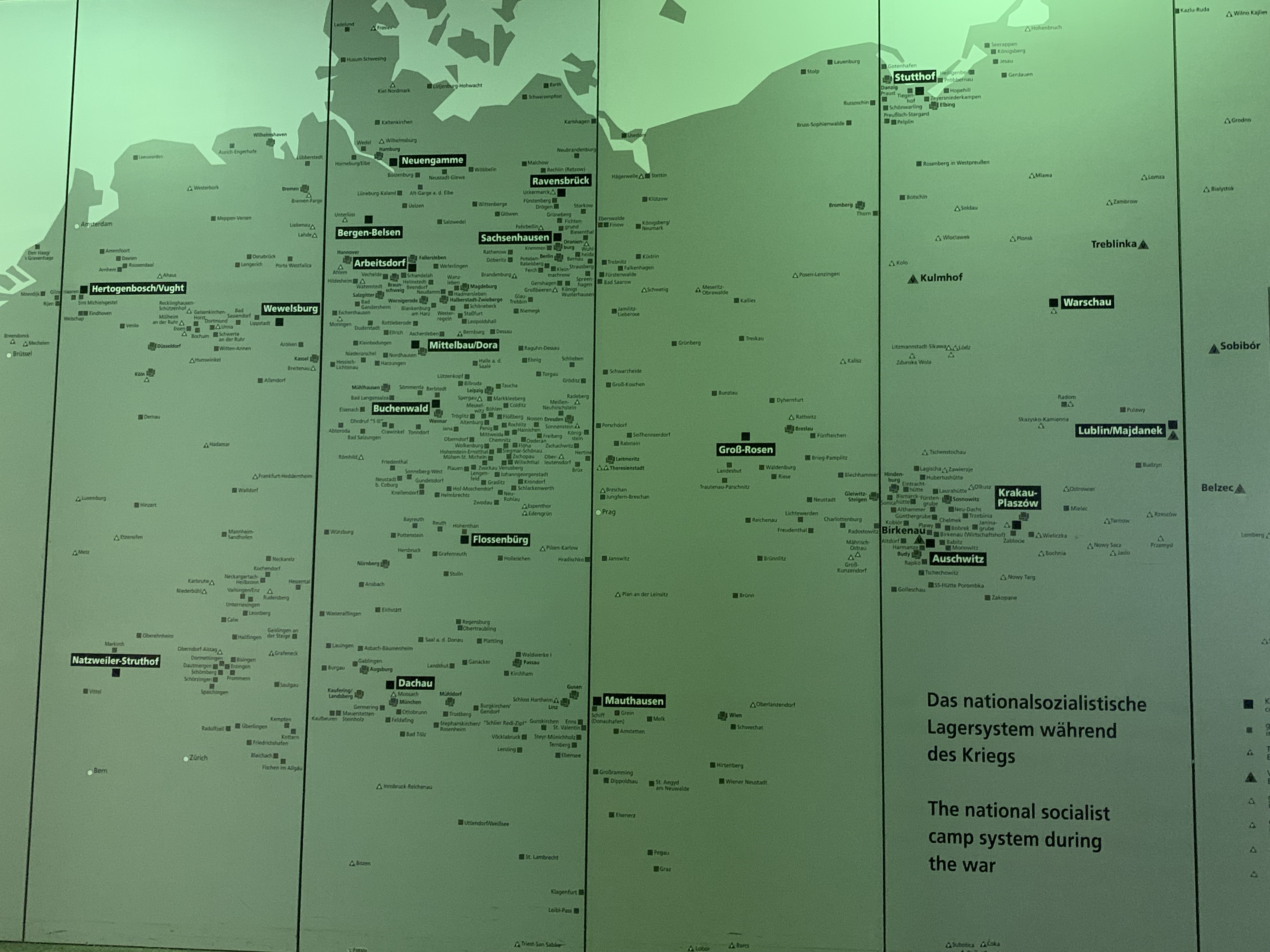

Dachau’s visit was not just about the past; it was about paying tribute to the resilience and suffering of our ancestors and countless innocent others. In 1938, with over 10,000 others, they endured the hardships of that awful place, while thousands more faced similar fates in Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, or sought refuge abroad.

During our time at Dachau, we received copies of the original records detailing their stay in the camp serving as a strong reminder of the struggles they endured.

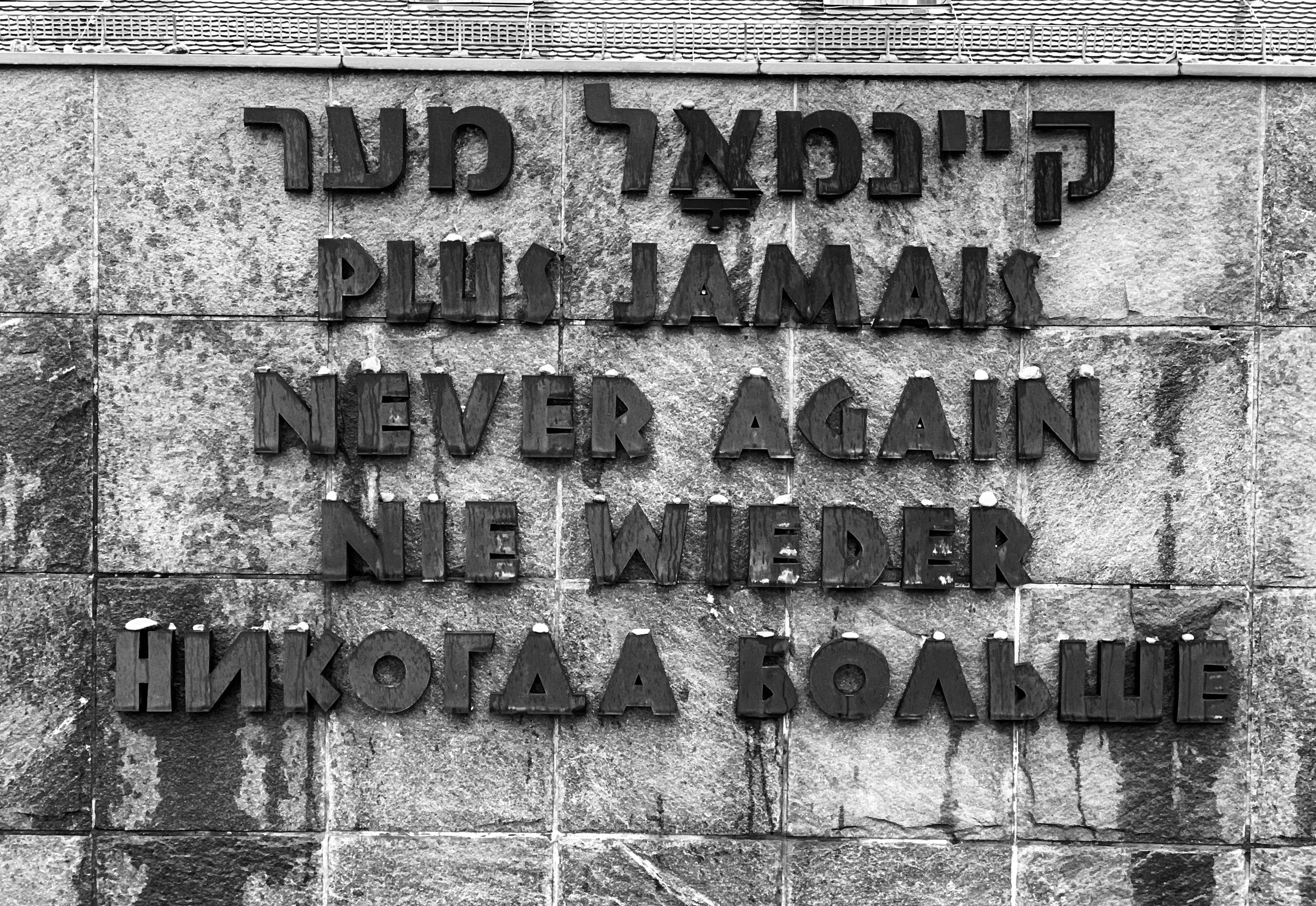

The visit deepened our connection to our family’s history. It was a somber way to acknowledge the past while embracing the importance of preserving the memories of those who endured and those who were lost.

In the end, our day at Dachau left a mark on our hearts and minds. It reinforced the importance of understanding history, no matter how painful, and reminded us to cherish our family’s journey while never forgetting the atrocities of the past.

Dachau, the first Nazi concentration camp established in 1933, held a dark and significant place in history. It served as a model for subsequent concentration camps across Europe and endured for twelve years.

The conditions within Dachau were deplorable, reflecting the cruelty and inhumanity of the Nazi regime. The camp was initially intended for political prisoners, but later expanded to incarcerate people from various backgrounds, including Jews, intellectuals, artists, and others deemed enemies of the state.

The camp became overcrowded as more prisoners were brought in leading to unimaginable suffering as resources were stretched thin, and the basic needs of the inmates, such as food and medical care, were neglected.

The horrors within Dachau extended beyond physical deprivation. Inmates faced torture, abuse, and forced labor, subjecting them to unspeakable cruelty on a daily basis. The psychological toll was immense, leaving scars that lasted long after the camp’s liberation.

On November 9th, 1938 my grandfather was with some of his friends when the Gesapo came in and arrested them because their names were on a “list”. He didn’t know what was happening, his name wasn’t on the list, so they let him go. Close to midnight that same night, the Gestapo showed up at my grandfather’s home in Lörrach – beat him, arrested him, and took him to jail. He was taken by train and then freight car, along with all the other Jewish men of the Baden area (including my grandmother’s father and uncles), and brought to Dachau, right outside Munich. We learned that this pogrom, later called Kristallnacht, was in retaliation for a 17 year old Polish Jew who had shot a German diplomat because he was upset that his parents, Polish Jews who lived in Germany for decades, had been deported back to Poland. The Jewish men and families were told that they were being brought to these camps for “protective custody” against the townspeople.

On November 9th, 1938, my grandfather’s life took a drastic turn. At the house of friends from the synagogue at the time, the Gestapo stormed in and claimed their names were on a “list.” Miraculously, his name wasn’t among them, and they allowed him to go free. Little did he know that the nightmare was far from over.

Close to midnight that same night, the Gestapo went to his home in Lörrach. Subjected him to a brutal beating, and tore him away from his family and locked him up in jail. Alongside other Jewish men from the Baden area, including his father-in-law, and wife’s uncles, he was then transported by train and freight car to a place he had never imagined – Dachau, just outside Munich.

It became known as Kristallnacht or the Night of Broken Glass, an act of retaliation for the tragic shooting of a German diplomat by a Polish Jew. But for him and the other innocent Jewish men and families, the official excuse was “protective custody” against the townspeople.

The reality that awaited them at Dachau was beyond comprehension. The conditions were horrifying, with overcrowding, torture, scarce food, and inadequate medical care. Forced into labor, they endured unspeakable cruelty day after day.

Our Visit…

When we arrived at Dachau, the walk from the parking lot to the camp entrance felt surreal. My grandfather’s recollections echoed in our minds as he had spoken about the walk from the train to the camp, unaware of the dreadful fate that awaited him.

The bridge my grandfather mentioned, where SS officers callously knocked prisoners into the water, held significant importance for us. We were anxious to find it, to witness the place that had left a lasting impact on his memories. Though the bridge we discovered wasn’t quite as imposing as we had imagined, it still bore witness to the atrocities of the past.

Passing through the iron gate with the chilling sign, “Arbeit Macht Frei,” sent shivers down our spines. It was the same gate our grandfather and thousands of others had walked through, only to face uncertainty and despair.

As we stood on the same ground my relatives once stood on 80 years ago, the size of the Paradeplatz surprised us. Its vastness, the size of two football fields, seemed to magnify the weight of their suffering. The pouring rain and puddles evoked the harsh conditions they endured during the relentless roll calls, always punished for minor infractions.

In that haunting place, we struggled with the cruelty that had been inflicted upon these prisoners. How could human beings devise and carry out such a dehumanizing plan?

As we walked through the camp, we were transported back to that dark, cold, and rainy November day, 80 years ago, when our relatives entered Dachau. The weight of history was palpable,.

Inside the camp, there was an excellent visitor center and museum, chronicling the history of the Nazi regime. The exhibits provided a account of the atrocities committed during that dark period, shedding light on the harrowing experiences of those who suffered.

The museum was full of valuable information, offering insights into the lives of the prisoners, the conditions they endured, and the resilience they displayed. Memorials dedicated to the victims served as poignant reminders of the lives lost and the need to remember their stories.

Walking through the former prisoners’ camp, we encountered a haunting sight – one barrack (dormitory) still stood, a somber relic of the past. The barracks, once crowded with prisoners, stood as silent witnesses to the suffering endured within those walls.

The camp itself was enclosed by imposing walls and watchful guard towers, a stark reminder of the oppressive control the Nazis exercised over the lives of those imprisoned there. Nearby, the buildings that once housed torture chambers, crematoriums, and a chilling gas chamber – though never used – stood as grim reminders of the horrors inflicted on innocent lives.

Inside the camp’s administration office, we were surprised by the wealth of resources available. The library housed a collection of books and records, providing valuable insights into the camp’s history and the lives of those who had been imprisoned there.

Upon our arrival, the staff warmly welcomed us, aware of our visit and the significance it held for our family. They kindly offered us the use of their conference room for the day, understanding the emotional journey we were embarking on.

As we sat down in the conference room, they brought the records they had collected about our family members who were once inmates at Dachau.

Their efforts to preserve the stories of those who had suffered under the Nazi regime served as a testament to the importance of remembering and understanding the past.

The day spent in Dachau brought us closer to our family’s history, allowing us to pay homage to our ancestors and to reflect on the impact of that dark chapter in their lives. Armed with this newfound knowledge, we left Dachau with a profound sense of responsibility to ensure that their stories are never forgotten and that the lessons of history continue to guide us towards a future of compassion, tolerance, and understanding.